Subscription Pricing: Subtle persuasion that works

These days it seems like everyone listens to Spotify. They have over a 100 million paying customers worldwide despite a free tier. A monthly subscription in the US costs $9.99 for a single account and $12.99 for two. What makes their pricing appealing to so many?

We all know to a varying degree that pricing can be used to shape our purchasing decisions. When was the last time you bought something because it was either: on sale, sold as a “limited time” offer, or offered at a trial price? Similarly, subscriptions have a seemingly magical and subtle property of making things appear more affordable. Ten dollars a month to Spotify doesn’t sound like a lot. Since subscriptions have become so popular the last few years, even more so since the pandemic, I thought an interesting and relevant exercise would be to look at a few examples to see how their pricing may be designed to influence our choices. Of course, to do this one has to understand how they are priced, so please indulge me for just a wee bit while I provide a little background.

…Or skip ahead and go directly to the examples (New York Times, Netflix, Bloomberg) if the last sentence triggered a snoozefest alarm in your head or flashbacks to econ 101 (I get it).

The pricing function

A common misconception about pricing is that it fulfills a kind of economic need. True, a company’s sales must eventually cover expenses, but for that to happen a more fundamental problem of convincing people to buy needs to first be addressed. Price in this regard, is really a business tool to help drive demand. As a consumer, you may have a perception that price generally equals value, but it certainly doesn’t have to. Value is in the eye of the beholder (Yeezy shoes, …“holy schnikes!”).

In driving demand, price indicates a company’s estimate of a customer’s willingness to pay (WTP). Since companies aim to maximize revenue, the WTP consideration needs to:

- Appeal to the greatest number of target customers

- Extract the maximum amount of revenue from each customer

Sometimes this dynamic is balanced in a single price point and in other times accommodated with multiple (Netflix).

The price setting process - three main components

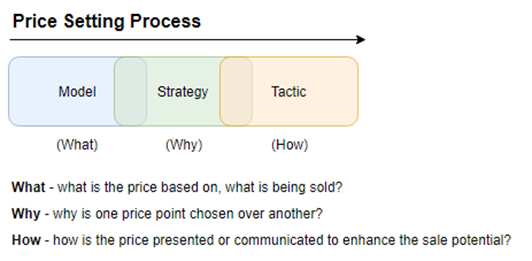

The price a customer ultimately sees is the result of a price setting process. Various industries and companies will go about this in different ways. For subscription services, pricing is usually a product of a Pricing Model and a Pricing Strategy. These terms are often used interchangeably but are conceptually different and really belong to separate buckets (definitions below). A third bucket, Pricing Tactic, is usually lumped under pricing strategy as a psychological pricing strategy but is worth breaking out separately since it usually has more to do with tactics at the presentation layer rather than as a price setting function.

These buckets are loosely defined as follows:

Pricing Model - Generally relates to the product or service itself and some metric by which is it sold. Is it usage based? Priced per user? Priced per feature? Sold as a package, plan, or tier with pricing segmented into different levels (ex, standard, professional, enterprise, etc.)? These are all elements of the pricing model.

Pricing Strategy - Generally relates to price considerations in the product or service’s competitive environment. For example, Penetration Pricing is often employed as a strategy to gain market share by temporarily offering lower prices to quickly attract customers. Captive Pricing on the other hand, is common when the switching cost is high (i.e., something is not easily substituted). Common examples include: pricing on movie concessions, printer ink, and product accessories like chair ottomans and washing machine stands.

Pricing Tactic - Generally has a psychological component present in the way pricing is presented to the customer. The $x.99 pricing example everyone is so familiar with is often called Charm Pricing. It works - quick, double $9.99. If you weren’t paying attention, you have said $18. Price Anchoring is another example where a higher priced item is placed next to the item being sold to make it appear cheaper.

Together, each bucket - model, strategy, and tactic - clarifies at a high level the what, why, and how of pricing from the seller’s perspective. This is illustrated below (note: buckets can and do sometimes overlap).

Pricing practices in the wild

If you made it this far, thanks! Lecture time is over, let’s get into a few examples.

The New York Times

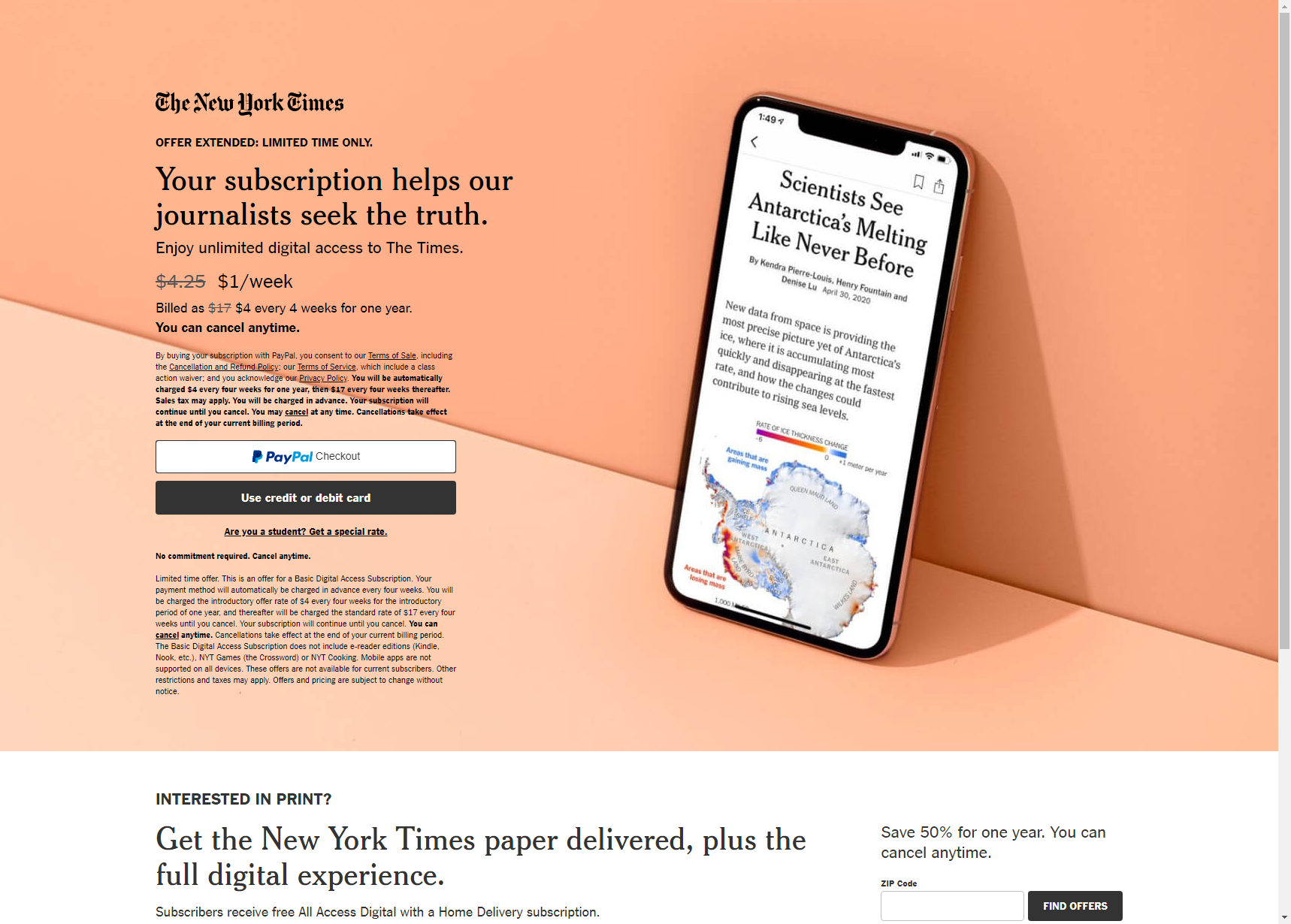

I’ll lead off this section with a question about the New York Times. What sounds more agreeable, spending $221 on a 1 year subscription for online access to their reporting or paying the equivalent of $1 a week, and being billed $4 every 4 weeks for the same access? In fact, here’s their pricing information (as of 05/01/21):

You are of course, supposed to think $1 a week is a pretty good deal (…maybe I do?). Nowhere does it actually say $221 a year, though that is the equivalent amount you would spend annually if you continued with a subscription after the initial one-year trial rate. We’ve all seen introductory pricing as a sales tactic before, but there are a few other less obvious tactics employed on this page worth mentioning.

You probably observed the standard price was shown first, crossed out, then the trial price is displayed. This is a psychological tactic called Price Anchoring and is intended to make the trial price more appealing from a comparative value perspective ("I’m saving $3.25 a week? That’s a good deal!").

Also, the price is listed on a weekly basis while the billing cycle is not. This is a form of price reframing used to make the product sound cheaper. A $1 a week payment rate certainly sounds better than paying $52 a year (at the trial price). They are of course equivalent. This is also why $221 is never mentioned anywhere as the annual price, it sounds expensive.

The most subtle aspect of their pricing may be the billing frequency. Most subscription plans, especially time-based ones, are either billed in monthly or yearly cycles, so their “every 4 weeks” seems a little odd. They might have a plausible sounding reason for using that metric, but this also seems like a good time to apply Occam’s Razor. Whenever I see “4 weeks” I usually interpret that to be roughly a month’s time and if I were time pressed while reading their ad (many people are), I might mistakenly interpret it to mean monthly billing. There are of course 52 weeks in a year which would mean 13 billing cycles (52/4). The simplest explanation therefore, seems to be 4 weeks is used to hide an extra payment cycle. Put another way, that’s a pricing dynamic that works to the Times’s advantage and is unlikely to have internally gone unnoticed.

Let’s take a look at another example.

Netflix

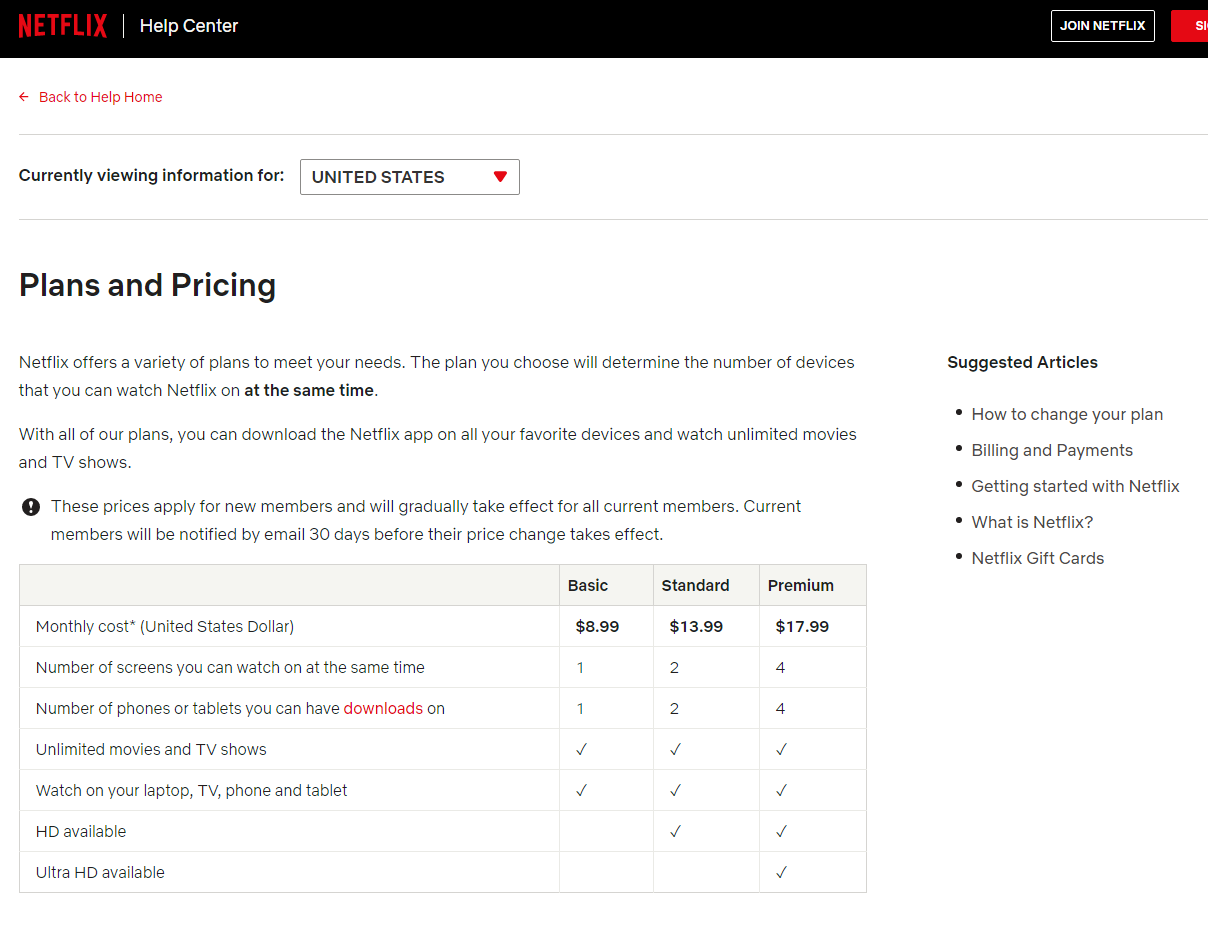

Here’s Netflix’s pricing page (as of 05/01/21):

On the surface their pricing is unremarkable. They use a tiered pricing model with Basic, Standard, and Premium plans available. Each plan has a single price point, charged monthly, that uses Charm pricing. …Who hasn’t seen this before? Ok, maybe a strategy will become more apparent with some additional thought.

Subscriptions using tiered pricing are quite popular and one explanation given for their prevalence is the plans allow customers to self-select into service levels that are right for them. In theory this attracts more customers and helps a company increase revenues. No argument with that, but it also glosses over another reason companies like tiered plans so much. They allow them to use Decoy Pricing to nudge customers into a higher price level. Paul Olyslager does a good job explaining how this works here, but in short, the plans are designed force a customer to make a comparative choice between options that usually guide customers towards the company’s preferred plan.

Netflix’s Basic plan does not include HD streaming, but almost any device (TV, laptop, tablet, mobile phone, kids toys, etc.) produced in the last six or so years is capable displaying HD content. If you can get an HD picture chances are you are going to want it. Of course, not everyone can get HD content. Many rural areas in the US have internet speeds less than 5 Mbps (the minimum for HD streaming) and some internet plans are metered, which means those people are unlikely to want HD streaming. Still, if a little over three-quarters of American adults have broadband at home and if only 1 out of every 6 Americans lives in a rural area, demand for the basic plan is unlikely to ever be very strong. If 10% of Netflix’s US customers signup for the basic plan at current prices that would only represent roughly 6% of their US revenue. That’ not exactly a segment that will be moving their stock price much.

Removing charm pricing from Netflix’s plans makes it easier to see the Premium plan ($18) is priced 2x the Basic plan ($9) and the Standard plan ($14) is skewed closer to the premium pricing. Netflix knows not everyone will want or need the premium plan so it seems pretty clear they expect the majority of customers to select into the standard plan and they’ve priced it accordingly. On the whole, their pricing looks to be a textbook play of a) attracting as many target customers as possible with the low price point on the basic plan, and then b) get more money out of each customer by having the majority self-select into a higher plan.

Bloomberg

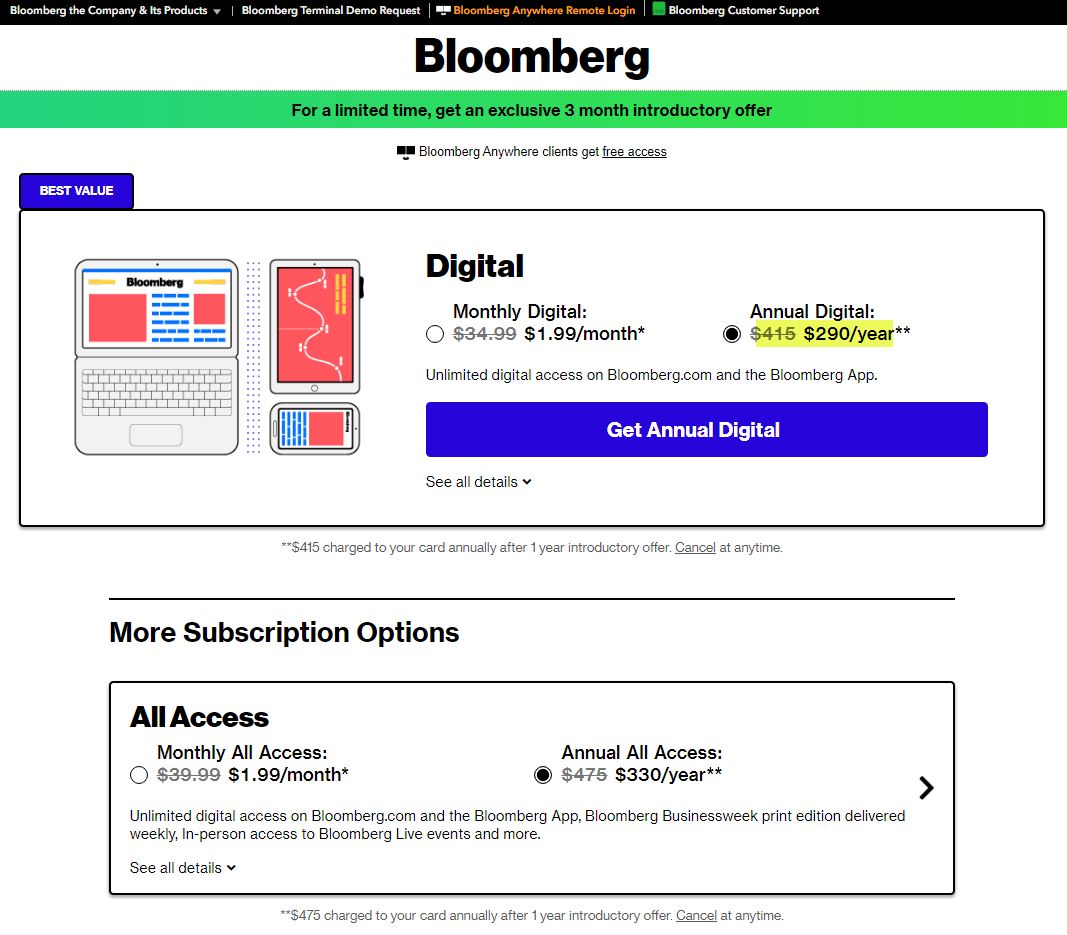

I initially wasn’t planning to include another news media service in this post but the pricing on a Bloomberg News subscription proved to be too compelling (yes, the pricing, really). The short of it is they appear to employ a price discrimination strategy to maximize revenue. In other words, different pricing is offered to different people (or categories of people) based in part on their willingness to pay. So tricksy and irresistible, right?!

To see this at work, let me first give a little background. News on their website was free until they decided to paywall it in 2018 by introducing two different subscription plans. The Digital plan gave the user unlimited access to everything on the bloomberg.com domain and was priced at $34.99 a month or $415 a year, while the All Access plan, which included Digital and other perks, was priced at $39.99 a month and $475 a year. Not exactly cheap, but much of their readership is built-in given their prominence in financial services (many who could probably expense a subscription - something assuredly not lost on Bloomberg) so the price premium is not terribly surprising.

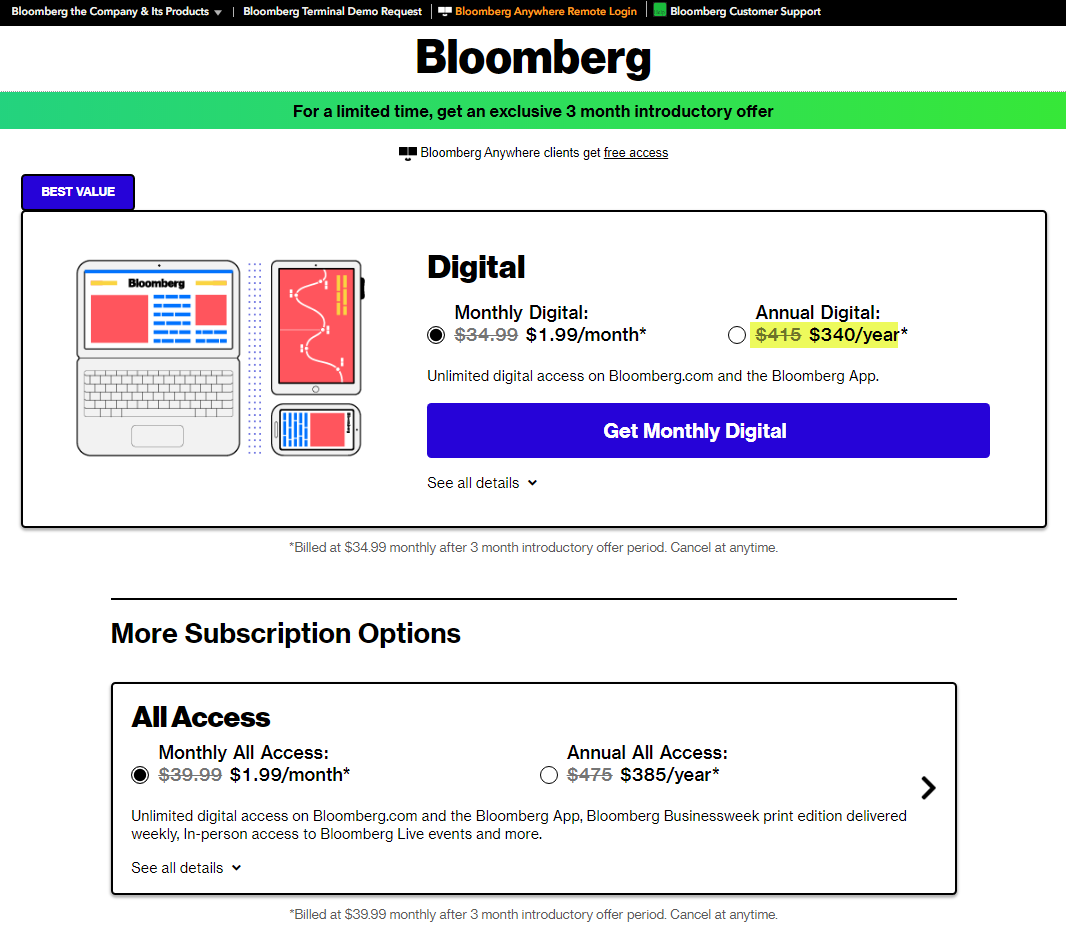

If you visit Bloomberg’s main page today and click the subscribe button in the upper right corner you’ll see the same regular price points listed above along with a discounted trial offer. It may even be the same as what’s pictured below (…I sometimes saw different offers):

Of course, going in through Bloomberg’s front door is just one way to access pricing. Emailed offers (with links), article read limit notifications, and search results could be other entrance points leading to the same information Or they could take you to other promotions not ordinarily available. This in and of itself is not very surprising, but the variety of pricing I was able to find above and below the $290 price point on the Annual Digital example above is what I found so interesting. Note: since the Digital plan is Bloomberg’s main subscription product (All Access represents the upsell opportunity), all price points in the discussion below, unless specified, are in context of the Digital plan.

The below is a search result referencing Bing as the referral source (plus a couple other UTM parameters embedded in the URL) that offers a worse first year trial price of $340 instead of the $290 above.

With a little digging, I was able to uncover a variety of different pricing campaigns. They generally seem to fall into three campaign groupings I’ll creatively call campaigns 1,2, and 3 and appear follow two different strategies. Campaign 1 focuses on varying the monthly trial price while campaign 2 varies the annual trial price. The strategy for both attempts to lure customers with attractive trial pricing that eventually converts to standard pricing once the trial period has ended. This is ultimately more profitable for Bloomberg and thus presumably why I saw them with much more frequency than those in campaign 3. Here’s a few campaign 1 and 2 examples:

- Campaign 1 - Offer introductory discounts on monthly plans only, do not show the annual option, standard pricing applies after original three-month introductory period. Monthly offers at: ($9.99/month or $1.99/month).

- Campaign 2 - Offer one-year introductory pricing on annual plan, also offer introductory discounts on monthly plans, standard pricing applies after expiration of trial period (Annual offers at: $340, $290, $240, $203(uses a countdown timer), $199).

Campaign 3 takes a different tack and focuses instead on varying the standard monthly price. A three-month trial price of $1.99 is offered but instead of reverting to a regular monthly price of $34.99 at the end of the trial period, a different “standard” price is offered. Here’s the progression:$29.99, $19.99, $14.99, $9.99).

Other General Observations:

- Monthly pricing always used charm pricing while annual never did.

- In virtually all examples, a price decoy (the same pricing) was used on monthly trial pricing for the Digital and All Access plans in the hopes the customer would “logically conclude” the All Access plan was the better value for the same money…while costing more in the long run.

- Standard monthly pricing for Campaign 3 offers was always better than the standard annual price. At $19.99 and below, the monthly price even beat the trial annual price. This would be easy to miss if you didn’t mentally run the numbers.

Bloomberg’s pricing in a way looks a lot like a tiered pricing plan. The difference between their pricing and Netflix’s is Bloomberg controls who gains access to the various price points. The bulk of customers end up paying the standard digital rates (34.99/monthly, $415/annual), a lucky few are paying a monthly $9.99 rate ($119.88 annualized), and I suppose there’s even a few unlucky souls paying slightly more than standard ($420/year). However it breaks down, I would love to see their internal conversion numbers.

Wrap up

I hoped to show in this post some of the less familiar ways subscription pricing can be designed to influence our purchasing choices. Of course, three examples only scratch the surface in terms of what’s out there. Is pricing interesting? I suppose that is a matter of perspective.

As for Spotify, I don’t know. My wife and I don’t need our own accounts. But if I can easily filter out all of my daughter’s playlists by getting a second account …for only $3 more a month? That just might be worth it.

Recap of pricing concepts discussed:

- Captive Pricing

- Charm Pricing

- Decoy Pricing

- Penetration Pricing

- Price Anchoring

- Price Discrimination